*this article contains some light spoilers

“Your role in social change starts two steps past where you’re comfortable.”

Both times I’ve watched “Get Out” have left me disturbed and sleeping uneasily. Not to be over dramatic about it. I am generally scared of the dark and what lurks behind shower curtains, but “Get Out’ isn’t that type of horror movie (now I'm afraid of people stirring cups of tea.) It elicits a unique mixture of being disturbed by the realities depicted, yet comforted by the common experiences the film brings to light.

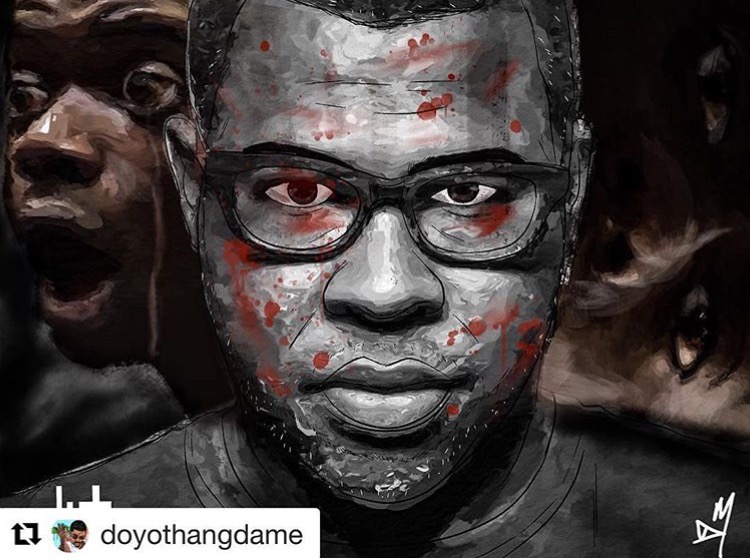

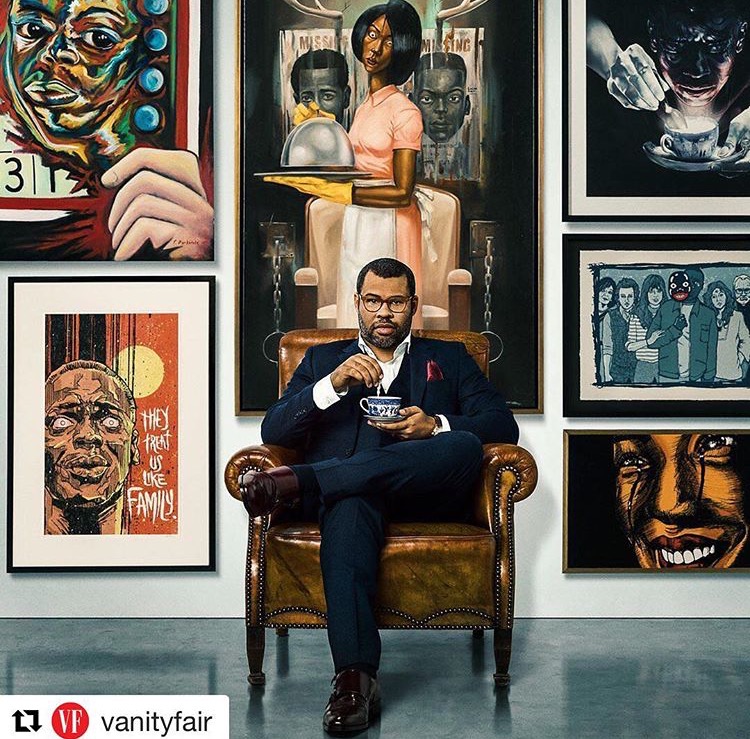

There’s not much debate to be had about the impact of Jordan Peele’s directorial debut. Over the past weekend (it’s second since being released) “Get Out” made Peele the first Black writer/director whose debut film made over $100 million. It says even more when it’s noted that the film was made on a $4.5 million budget, and focuses on subject matter that many would reasonably doubt could even be broached in a major Hollywood film. Beyond dollars, the film’s impact is reflected in the amount of fan art that has been inspired. Imagery that demonstrates how vividly the ideas in “Get Out” have resonated with artists.

There are some banging pieces out there on the meaning and implications of this movie. Son of Baldwin has written one and linked to many others here. Some of my personal favorite aspects of “Get Out”:

- Sick, genius level attention to detail. This has to have contributed to the massive box office success. A movie that’s worth seeing more than once in the theater is rare. The detail is so smart and clever, it takes multiple viewings to catch it.

- Ignoring or laughing off the less overt racism. Chris repeatedly does this. Many of us do the same. We’ve gotten to a place in society where Black people don’t react to micro-aggressions because we’d be reacting all day. We’re trained, subconsciously or not, to protect white fragility. Meanwhile, other sub-groups overreact, with deadly consequences, to what they perceive as threats. Perceptions created by the racist imagery and propaganda that’s built into the fabric of America.

- Rose didn’t sit right with me from the moment she informed Chris that she hadn’t told her parents that he is Black. Even more egregious was Rose interjecting herself into Chris’ interaction with the police officer. A real thing that people oblivious to their own privilege do. It was repulsive.

- The opening scene and it’s demonstration of what kinds of neighborhoods are scary and uncomfortable for which people. This makes me think of all the “Best Places to Live” articles. Best for whom?

- The beyond creepy scene where Rose is eating her multi-colored fruity O’s separate from her white milk. The whitest thing about it was her biting her pieces of cereal in half, and bumping the music from Dirty Dancing. Artful display of creepy, real, and funny at the same time.

Something outside the movie itself that I’ve found interesting are comments here and there expressing surprise that Jordan Peele, a Black man with a white mother and a white wife, has created such unsympathetic white characters. Seriously, there are zero redeeming white people in the movie. How often does that happen in Hollywood? Based on interviews, it seems that Peele’s specific racial identity and experiences are a huge part of what facilitated his conception of this film. That suggestion that the child of a white woman would not create honest critique culture and race in America is kind of crazy, but because white supremacy, this kind of idea isn’t new or rare. People still believe that proximity to whiteness in ones upbringing is not only desirable but protective against the realities of being Black in America. Proximity, including geography, skin tone, family status, speaking patterns… are things that confer privilege in our society. These things are also part of what creates the breadth of the Black experience—they certainly don’t mean you’re not still Black in America.

The undertone is that if a person has the option (through their skin color, education level, economic status, etc.) to diminish or downplay their Blackness and assimilate, that would be the desirable choice. If one could choose whiteness, or closer to white, it would be a logical. That because you experience light-skinned privilege you are going to be complicit in white-supremacist ideology and let the bullshit slide. Essentially going into “The Sunken Place.”

On a personal note, I have experienced being accused of “forgetting where I came from,” in a way that is contrary to the more common narrative of a Black person ‘making it’ and leaving their heritage behind. Rather, the accusation is based on being raised by my white mother, yet speaking about racial justice or identifying as Black. My personal struggle is to define myself for myself, despite the constraints of a white supremacist society. Because whiteness and lightness is privileged, claiming it feels like a form of complicity—even though that is in fact part of my identity. Jordan Peele had a bit about “coming out” as Bi-racial. I personally am most comfortable identifying as multiracial Black, but most frequently as Black. My identity is in no way conceived of by me forgetting from whence I came.

Part of where I come from is visiting a white childhood friend’s home, only to have her mother dive into a speech about the Black people who work for them, how Black people work so hard, and that Black people have SUCH NICE TEETH.

Part of where I come from is having a coach get grease smeared on her clothes from some equipment and telling me, the only Black child, “it must have rubbed come off you.”

Part of where I come from is having a friend’s neighbor say, “Black people are greasy,” and my 11 year-old self not knowing what to do, responding with, “no, white people are greasy,” to which this grown ass white woman slapped me across the face.

(The ironic part about this grease theme is that I most likely had the driest hair around, since no one was moisturizing it properly.)

Again, proximity to whiteness is not protective against white supremacist America. These happenings in my girlhood aren’t unique, they are part of the fabric of the Black experience. Having a white parent, growing up around white people, does not protect from this or diminish a person’s awareness of their Blackness. In many cases it heightens it. Heightened awareness or not, the problematic extension of the idea that mixed race Black people shouldn’t speak and act in the interest of justice is that white people also shouldn’t. Wrong. People in positions of privilege bear an even greater responsibility. A responsibility that Peele apparently takes seriously and has given us the gift of “Get Out.”

“Part of the desire to live in a post-racial world includes the desire not to have to talk about racism, which includes a false perception that if you are talking about race, then you’re perpetuating the notion of race. I reject that.”